Religion in Australia

In the 21st century, religion in Australia remains dominated demographically by Christianity, with 64% of the population claiming at least nominal adherence to the Christian faith as of 2007, although less than a quarter of those attend church weekly.[1] 18.7% of Australians declared 'no-religion' on the 2006 Census, (with a further 11.2% failing to answer the question)[1][2] and the remaining population is a diverse group that includes fast-growing Islamic and Buddhist communities.[3]

The Australian Constitution prohibits the Commonwealth government from establishing a church or interfering with the freedom of religion; however, states are free under their own constitutions to interfere or establish a church as they see fit, although none ever has. Nevertheless, the relationship between the Commonwealth government and religion is much freer than in the United States, with governments working with religious organisations that provide education, health and other public services.

Contents |

History

At the time of European settlement, the Indigenous Australians had their own religious traditions of the Dreamtime (as Mircea Eliade put it) There is a general belief among the [indigenous] Australians that the world, man, and the various animals and plants were created by certain Supernatural beings who afterwards disappeared, either ascending to the sky or entering the earth [5] and ritual systems, with an emphasis on life transitions such as adulthood and death [6].

Prior to European settlement in 1788 there was contact with Indigenous Australians from people of various faiths. These contacts were with explorers, fishermen and survivors of the numerous shipwrecks. There has been countless artifacts [7] retrieved from these contacts. The Aboriginals of Northern Australia (Arnhem Land) retain stories, songs and paintings of trade and cultural interaction with boat-people from the North. These people are generally regarded as being from the east Indonesian archipelago. (See: Macassan contact with Australia.) There is some evidence of Islamic terms and concepts entering Northern Aboriginal culture via this interaction.[8][9]

Centuries before European sailors reached Australia, Christian theologians already speculated whether this region, located on the opposite side of the Earth from Europe, had human inhabitants, and if so, whether these Antipodes have descended from Adam and have been redeemed by Jesus. The prevailing point of view, expressed by Augustine of Hippo was that "it is too absurd to say that some men might have set sail from this side and, traversing the immense expanse of ocean, have propagated there a race of human beings descended from that one first man."[10][11] A dissenting view, held by the Irish-Austrian St. Vergilius of Salzburg was "that beneath the earth there was another world and other men"; while not much is known about Vergilius' views, Catholic Encyclopedia speculates that he was able to clear himself from accusations of heresy by explaining that the people of the hypothetical Australia were descended from Adam and redeemed by the Lord.[12]

By the early 18th century, Christian leaders felt that the natives of the little known "Terra Australis Incognita" and "Hollandia Nova" (still often thought as two distinct land masses) are in the need of conversion to Christianity. In 1724, a young Jonathan Edwards wrote:

... And what is peculiarly glorious in it, is the gospelizing the new and before unknown world, that which is so remote, so unknown, where the devil had reigned quietly from the beginning of the world, which is larger – taking in America, Terra Australis Incognita, Hollandia Nova, ... – is far greater than the old world. I say, that this new world should all worship the God of Israel, whose worship was then confined to so narrow a land, is wonderful and glorious! [13]

Christianity was introduced with the First Fleet.[14] Denominations represented were predominantly Roman Catholic found amongst Irish convicts and Anglican among other convicts and their gaolers. Other groups were also represented, for example, among the Tolpuddle Martyrs were a number of Methodists. The First Fleet brought tensions to Australia fuelled by historical grievances between Protestants and Catholics, tensions that would continue into the 20th century.[14]

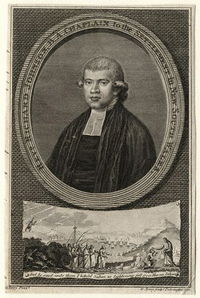

The first chaplain, Richard Johnson, a Church of England minister was charged by Governor Arthur Phillip with improving 'public morality' in the Colony, but he was also heavily involved in Health and Education[15]. Christian leaders have remained prominent in health and education in Australia ever since, with over a fifth of students attending church schools at the beginning of the 21st century and a number of the nation's hospitals, care facilities and charities having been founded by Christian organisations.[16]

After settlement, some Muslim sailors and prisoners came to Australia on the convict ships, Afghans cameleers settled in Australia from the 1860s onwards, a number of them being Sikh, from the 1870s Malay divers were recruited (with most subsequently repatriated). Islam was not a significant minority in this period.

During the 1800s, European settlers brought their traditional churches to Australia. These included the Church of England and the Methodist, Catholic, Presbyterian, Congregationalist and Baptist churches.

The Church of England was disestablished in the Colony of New South Wales by the Church Act of 1836. Drafted by the reformist attorney-general John Plunkett, the act established legal equality for Anglicans, Catholics and Presbyterians and was later extended to Methodists.[17]

Freedom of Religion was enshrined in the Australian Constitution of 1901. At the establishment of the federation - apart from a small Lutheran population of German descent, the indigenous population, and the descendants of gold rush migrants - Australian society was predominantly Anglo-Celtic, with 40% of the population being Anglican (then Church of England), 23% Catholic, 34% other Christian and about 1% professing non-Christian religions. The first census in 1911 showed 96 percent identified themselves as Christian. The tensions that came with the First Fleet continued into the 1960s: job vacancy advertisements sometimes included the stipulation that 'Catholics Need Not Apply'.[14] Nevertheless, Australia elected its first Catholic prime minister, James Scullin, in 1929 and Sir Isaac Isaacs, a Jew, was appointed governor-general in 1930.[18][19]

Further waves of migration and the gradual repeal of the White Australia Policy, helped to reshape the profile of Australia's religious affiliations over subsequent decades. The impact of migration from Europe in the aftermath of World War II led to increases in affiliates of the Orthodox churches, the establishment of Reformed bodies, growth in the number of Catholics (largely from Italian migration) and Jews (Holocaust survivors) and the creation of ethnic parishes among many other denominations. More recently (post-1970s), immigration from South-East Asia and the Middle East has expanded Buddhist and Muslim numbers considerably and increased the ethnic diversity of existing Christian denominations.

As has been the trend throughout the world since the terrorist attacks of September 11, there has been an increasingly strained relationship between the adherents of Islam and the wider community. Attempts have been made to bridge inter-faith differences. However, the influence of the identity politics as a whole is not to be discounted in this respects; reflected in the conflicting and ambiguous interpretation of the 2005 race riots in Cronulla, near Sydney.

Religious places of worship have made their mark on Australia. Churches or chaples have been constructed in most towns, with many fine Cathedrals built in the Colonies during the 19th Century. Synagogues, Mosques and Temples are also a feature of most Australian cities and Australia has both the oldest Mosque and largest Buddhist Temple in the Southern Hemisphere

Constitutional status

Section 116 of the 1900 Act to constitute the Commonwealth of Australia (Australian Constitution) provides that:

The Commonwealth of Australia shall not make any law establishing any religion, or for imposing any religious observance, or for prohibiting the free exercise of any religion, and no religious test shall be required as a qualification for any office or public trust under the Commonwealth.

In 1983, the High Court of Australia defined religion as a complex of beliefs and practices which point to a set of values and an understanding of the meaning of existence. The ABS 2001 Census Dictionary defines "No Religion" as a category of religion which has sub categories such as agnosticism, atheism, Humanism and rationalism.

The Human Rights and Equal Opportunity Commission (HREOC) is able to inquire into allegations of discrimination on religious grounds.

HREOC's 1998 [20] addressing the human right to freedom of religion and belief in Australia against article 18 of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights stated that despite the legal protections that apply in different jurisdictions, many Australians suffer discrimination on the basis of religious belief or non-belief, including members of both mainstream and non-mainstream religions, and those of no religious persuasion.

Many non-Christian adherents have complained to HREOC that the dominance of traditional Christianity in civic life has the potential to marginalise large numbers of Australian citizens. An example of an HREOC response to such views is the IsmaU project[21], which examines possible racial prejudice against Muslims in Australia since the 11 September 2001 attacks in the US, and the Bali bombings.

Demographics

A question on religious affiliation has been asked in every census taken in Australia, with the voluntary nature of this question having been specifically stated since 1933. In 1971, the instruction 'if no religion, write none' was introduced. This saw a sevenfold increase from the previous census year in the percentage of Australians stating they had no religion. Since 1971, this percentage has progressively increased to about 19% in 2006.

The Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) 2006 Census Dictionary statement on religious affiliation states the purpose for gathering such information:

Data on religious affiliation are used for such purposes as planning educational facilities, aged persons' care and other social services provided by religion-based organisations; the location of church buildings; the assigning of chaplains to hospitals, prisons, armed services and universities; the allocation of time on public radio and other media; and sociological research.

The 2006 census identified that 64% of Australians call themselves Christian: 26% identifying themselves as Roman Catholic and 19% as Anglican. Five percent of Australians identify themselves as followers of non-Christian religions, and 19% categorised as having "No Religion"; 12% declined to answer or did not give a response adequate for interpretation. As in many Western countries, the level of active participation in church worship is much lower than this; weekly attendance at church services is about 1.5 million, about 7.5% of the population.[22]

According to the census, the fastest growing religions during the intercensal period between 2001 and 2006 were: Hinduism by 55.1 percent, Non-religion by 27.5 percent, Islam by 20.9 percent, Buddhist affiliation increased by 17 percent, and Judaism by 6 percent. Christianity was the only religion to show negative growth, with the number of followers falling by 0.6 percent.

The largest population increase was Non-religion which increased by 800,563 people. Buddhism increased by 60,940 people, Islam by 58,819 people, Hindu by 52,660 people. Christianity was the only religion to decrease in population, decreasing by 78,513. During that same period the population of Australia increased by 1,086,044.

| 2006 | 2001 | % change (relative) |

% change (absolute) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number | % | Number | % | |||

| Roman Catholic | 5,126,884 | 25.8 | 5,001,624 | 26.6 | -0.8 | +2.5 |

| Anglican | 3,718,250 | 18.7 | 3,881,162 | 20.7 | -2.0 | -4.2 |

| Uniting Church in Australia | 1,135,423 | 5.7 | 1,248,674 | 6.7 | -1.0 | -9.1 |

| Presbyterian and Reformed | 596,668 | 3.0 | 637,530 | 3.4 | -0.4 | -6.4 |

| Orthodox | 544,162 | 2.7 | 529,444 | 2.8 | -0.1 | +2.8 |

| Baptist | 316,740 | 1.6 | 309,205 | 1.6 | 0 | +2.4 |

| Lutheran | 251,108 | 1.3 | 250,365 | 1.3 | 0 | +0.3 |

| Pentecostal | 219,689 | 1.1 | 194,592 | 1.0 | +0.1 | +12.9 |

| Other Protestant | 736,004 | 3.7 | 675,422 | 3.6 | +0.1 | +9.0 |

| Oriental Orthodox | 40,901 | 0.2 | 36,324 | 0.2 | 0 | +12.6 |

| Total Christian | 12,685,829 | 63.9 | 12,764,342 | 68.0 | -4.1 | -0.6 |

| Buddhist | 418,753 | 2.1 | 357,813 | 1.9 | +0.2 | +17.0 |

| Muslim | 340,397 | 1.7 | 281,578 | 1.5 | +0.2 | +20.9 |

| Hindu | 148,123 | 0.7 | 95,473 | 0.5 | +0.2 | +55.2 |

| Jewish | 113,876 | 0.5 | 98,125 | 0.5 | 0 | +5.8 |

| Other religions | 242,848 | 1.2 | 92,369 | 0.5 | +0.7 | +162.9 |

| No religion | 3,706,556 | 18.7 | 2,905,993 | 15.5 | +3.2 | +27.5 |

| Not stated/inadequately described | 2,223,959 | 11.2 | 2,187,688 | 11.7 | -0.5 | +1.7 |

| Total population | 19,855,293 | 100.0 | 18,769,249 | 100.0 | 0 | +5.8 |

Indigenous Australian traditions

Indigenous Australians have a complex oral tradition and spiritual values based upon reverence for the land and a belief in the Dreamtime. The Dreamtime is at once the ancient time of creation and the present day reality of Dreaming. There were a great many different groups, each with their own individual culture, belief structure, and language. These cultures overlapped to a greater or lesser extent, and evolved over time. The Rainbow Serpent is a major dream spirit for Aboriginal people across Australia. The Yowie and Bunyip are other well known dream spirits. At the time of the European settlement, traditional religions were animist and also tended to have elements of ancestor worship.

According to the 2001 census, 5,244 persons or less than 0.03 percent of respondents reported practising Aboriginal traditional religions. Aboriginal beliefs and spirituality, even among those Aborigines who identify themselves as members of a traditional organised religion, are intrinsically linked to the land generally and to certain sites of significance in particular. The 1996 census reported that almost 72 percent of Aborigines practised some form of Christianity and 16 percent listed no religion. The 2001 census contained no comparable updated data.[23]

Christianity

The churches with the largest number of members are the Roman Catholic Church in Australia, the Uniting Church in Australia, and the Anglican Church of Australia. The Pentecostal churches and charismatic movement are also present with megachurches being found in most states (for example, Hillsong Church and Paradise Community Church). The National Council of Churches in Australia is the main Christian ecumenical body.

| Australian Christian bodies |

|---|

|

Australian Interchurch

|

The Christian festivals of Christmas and Easter are national public holidays in Australia. Christmas, which recalls the birth of Jesus Christ is celebrated on the 25th of December, at the height of summer, and is an important cultural festival even for many non-religious Australians. The European traditions of Christmas Trees, Roast dinners, Carols and gift giving are all continued in Australia - though they might be conducted between visits to the Beach; and Santa Clause is said in song to be drawn on his sleigh by Six white boomer kangaroos[24].

In his welcoming address to the Catholic World Youth Day 2008 in Sydney, Prime Minister Kevin Rudd said that Christianity had been a positive influence on Australia: "It was the church that began first schools for the poor, it was the church that began first hospitals for the poor, it was the church that began first refuges for the poor and these great traditions continue for the future"[25]. Christian charitable organisations, hospitals and schools have played a prominent role in welfare and education since Colonial times, when First Fleet chaplain Richard Johnson was credited as "the physician both of soul and body" during the famine of 1790, and was charged with general supervision of schools[15]. Today, the Catholic education system is the second biggest sector after government schools, with more than 650 000 students (and around 21 per cent of all secondary school enrolments). The Anglican Church educates around 105,000 students and Uniting Church has around 48 schools.[2] Catholic Social Services Australia's 63 member organisations help more than a million Australians every year. Anglican organisations work in health, missionary work, social welfare and communications; and the Uniting Church does extensive community work, in aged care, hospitals, nursing, family support services, youth services and with the homeless.[2] Christian charities like the Saint Vincent de Paul Society, the Salvation Army, and Youth Off the Streets receive considerable national support; and religious orders founded many of Australia's hospitals, such as St Vincent's Hospital, Sydney, which was opened as a free hospital in 1857 by the Sisters of Charity and is today Australia's largest not-for-profit health provider and which trained leading Australian surgeons like Victor Chang [26].

Historically notable Australian Christians have included: Mary MacKillop - educator, foundress of the Sisters of St Joseph of the Sacred Heart and the first Australian to be recognised as a Saint by the Roman Catholic Church[27]; David Unaipon - an Aboriginal writer, inventor and Christian preacher currently featured on the Australian $50 note[28]; Archbishop Daniel Mannix of Melbourne - a controversial voice against Conscription during World War One and against British policy in Ireland[29]; Reverend John Flynn - founder of the Royal Flying Doctor Service, currently featured on the Australian $20 note[30]; Sir Douglas Nicholls - Aboriginal rights activist, athlete, preacher and former Governor of South Australia[31].

Sectarianism in Australia tended to reflect the political inheritance of Britain and Ireland. Until 1945, the vast majority of Catholics in Australia were of Irish descent, causing the Anglo-Protestant majority to question their loyalty to the British Empire. The first Catholic priests arrived in Australia as convicts in 1800, but the Castle Hill Rebellion of 1804 alarmed the British authorities and no further priests were allowed in the Colony until 1820, when London sent John Joseph Therry and Philip Connolly[32]. In 1901, the Australian Constitution guaranteed Separation of Church and State. A notable period of Sectarianism re-emerged during the First World War and the 1916 Easter Uprising in Ireland[29], but the significance of Sectarian division declined dramatically Post World War Two. There was a growth in non-religious adherence, but also a diversification of Christian churches (especially the growth of Greek, Macedonian, Serbian and Russian Orthodox churches), together with an increase in Ecumenism among Christians, through organisations such as the National Council of Churches in Australia[33]

Australia contains a number of notable Christian places of worship from the tall spires of St Mary's Cathedral, Sydney and St Paul's Cathedral, Melbourne to the smaller scale, inner city Wayside Chapel in Sydney, or the Outback Lutheran Mission Chapel at Hermannsburg, Northern Territory. Adelaide is known as the City of Churches.

Christian denominations:

- Anglican Church of Australia (formerly Church of England)

- Australian Christian Churches (formerly Assemblies of God in Australia)

- Baptist Union of Australia

- Christian City Churches

- Christian Outreach Centre

- Church of Christ

- Churches of Christ in Australia

- Fellowship of Congregational Churches

- CRC Churches International

- Lutheran Church of Australia

- Presbyterian Church of Australia

- Presbyterian Church of Eastern Australia

- Presbyterian Reformed Church (Australia)

- Roman Catholic Church in Australia

- Seventh Day Adventist Church

- The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints

- Uniting Church in Australia

Hinduism

Hindus are a religious minority in Australia of roughly 150,000 adherents according to the 2006 census.[34] In the 19th century, Hindus first came to Australia to work on cotton and sugar plantations. Many remained as small businessmen, working as camel drivers, merchants and hawkers, selling goods between small rural communities. The population increased dramatically from the 1960s and 1970s, and more than doubled between the 1996 and 2006 census to 148 000 people. Most were migrants, from countries such as Fiji, India, Sri Lanka and South Africa. These days many Hindus are well educated professionals in fields such as medicine, engineering, commerce and information technology. There are around 34 Hindu temples in Australia.[2]

Islam

The first interaction that Islam had with Australia was through the Muslim fishermen from Makassar in Indonesia who visited North-Western Australia long before 1788. This can be identified from the graves they dug for their comrades who died on the journey, which face Mecca in Arabia in accordance with Islamic regulations concerning burial, as well as evidence from Aboriginal cave paintings and religious ceremonies which depict and incorporate the adoption of Makassan canoe designs and words.[35][36]

Throughout the 19th century Muslims came to Australia in order to perform specialised labour jobs - most famously the 'Afghan' Cameleers, who used their camels to transport goods and people through the otherwise unnavigable desert and pioneered a network of camel tracks that later became roads across the Outback. Australia’s first mosque was built for them at Marree, South Australia in 1861[2]. Between the 1860s and 1920s around 2000 cameleers were brought from Afghanistan and the north west of British India (now Pakistan) and perhaps 100 families remained in Australia. Other outback mosques were established at places like Coolgardie, Cloncurry, and Broken Hill - and more permanent mosques in Adelaide, Perth and later Brisbane. A legacy of this pioneer era is the presence of wild camels in Outback and the oldest Islamic structure in the southern hemisphere, at Central Adelaide Mosque. Nonetheless, despite their significant role in Australia prior to the establishment of rail and road networks, the formulation of the White Australia policy at the time of Federation made immigration difficult for the 'Afghans' and their memory slowly faded during the 20th Century, until a revival of interest began in the 1980s[37].

In the early twentieth century, people of non-European descent were discriminated against in the Australian immigration system, through the White Australia policy, which restricted immigration of Asians, Indo-Aryans, Turkic peoples from Asia Minor and other non-Anglo European areas. In the 1920s and 1930s, Albanian Muslims and Bosnian Muslims were accepted due to their lighter European complexion, which was more compatible with the White Australia Policy.

Successive Australian Governments dismantled the White Australia Policy in the Post-WW2 Period. From the 1970s onwards, under the leadership of Gough Whitlam and Malcolm Fraser Australia began to pursue Multiculturalism[38]. Australia in the later 20th Century became a refuge for many Muslims fleeing conflicts including those in Lebanon, the former Yugoslavia, Iraq, Iran, Sudan and Afghanistan[39]. General immigration, combined with religious conversion to Islam by Christian and other Australians, and Australia's participation in UN refugee efforts has increased the overall Muslim population. Around 36% of Muslims are Australian born. Overseas born Muslims come from a great variety of nations and ethnic groups - with large Lebanese and Turkish communities.

Following the 11 September 2001 terrorist attacks, associations drawn between the political ideology of Osama Bin Laden and the religion of Islam have stirred debate in some quarters in Australia regarding Islam's relationship with the wider community - with some advocating greater emphasis on assimilation, and others supporting renewed commitment to diversity. The deaths of Australians in bombings by militant Islamic Fundamentalists in New York in 2001, Bali in 2002-5 and London in 2005; as well as the sending of Australian troops to East Timor in 1999, Afghanistan in 2001 and Iraq in 2003; the arrest of bomb plotters in Australia; and concerns about certain cultural practices such as the wearing of the Burkha have all contributed to a degree of tension in recent times[40][41]. . A series of comments by a senior Sydney cleric, Sheikh Taj El-Din Hilaly also stirred controversy, particularly his remarks regarding "female modesty" following an incident of gang rape in Sydney[42][43]. Australians were among the targets of Islamic Fundamentalists in the Bali bombings in Indonesia and attack on Australian Embassy in Jakarta and the South East Asian militant group Jemaah Islamiyah has been of particular concern to Australians[44].

The Australian government's Mandatory Detention processing system for asylum seekers, became increasingly controversial after the September 11 Terrorist Attacks. A significant proportion of recent Asylum seekers arriving by boat have been Muslims fleeing the conflicts in Iraq and Afghanistan and elswhere.

Some Islamic leaders and social commentators claim that Islam has suffered from unfair stereotyping[45][46][47] Violence and intimidation was directed against Muslims and people of Middle Eastern appearance during southern Sydney's Cronulla riots in 2005.

In 2005, the Howard Government established the Muslim Community Reference Group to advise on Muslim community issues for one year, chaired by Dr Ameer Ali[48]. Inter-faith dialogues were also established by Christian and Muslim groups such as The Australian Federation of Islamic Councils and the National Council of Churches in Australia[49]. Australia and Indonesia co-operated closely following the Bali-bombings, not only in law-enforcement but in improving education and cross-cultural understanding, leading to a marked improvement in relations[50]. After a series of controversies, Sheikh Taj El-Din Hilaly retired as Grand mufti of Australia in 2007 and was replaced by Fehmi Naji El-Imam AM[43].

Today, over 360,000 people in Australia identify as Muslim. with diverse communities concentrated mainly in Sydney and Melbourne. Since the 1970s Islamic schools have been established as well as more than 100 mosques and prayer centres.[2] Many notable Muslim places of worship are to be found in Australian cities, including the Central Adelaide Mosque, which was constructed during the 1880s; and Sydney's Classical Ottoman style Auburn Gallipoli Mosque, which was largely funded by the Turkish community and whose name recalls the shared heritage of the foundation of modern Turkey and the story of ANZAC[51]. Notable Australian Muslims include boxer Anthony Mundine; community worker and rugby league star Hazem El Masri; and academic Waleed Aly.

Judaism

The history of the Jews in Australia began with the transportation of 8 Jewish convicts aboard the First Fleet in 1788 when the first European settlement was established on the continent. Today, an estimated 110,000 Jews reside in Australia, the majority being Ashkenazi Jews of Eastern European descent, with many being refugees and Holocaust survivors who arrived during and after World War II.

The Jewish population has increased slightly recently by immigrants from South Africa and the former Soviet Union. The largest Jewish community in Australia is in Melbourne with about 60,000 followed by Sydney with 45,000 members. Smaller communities are dispersed among the remaining state capital cities.

Following the conclusion of the British Colonial period, Jews have enjoyed formal equality before the law in Australia and have not been subject to civil disabilities or other forms of state-sponsored antisemitism which exclude them from full participation in public life.

JewishCare is among Australia's largest and oldest Jewish aid organisations, conceived in 1935 to assist with Jewish migration from Nazi Germany, it is today still engaged in assisting migrants and other services[52]. Sydney's gothic design Great Synagogue, consecrated in 1878, is a notable place of Jewish worship in Australia. Notable Australian Jews have included the World War One General Sir John Monash who opened The Maccabean Hall in Sydney in 1923 to commemorate Jews who fought and died in the First World War and who is currently featured on the Australian $100 note[53]; and Sir Isaac Isaacs who became the first Australian born Governor General in 1930[19]. The Sydney Jewish Museum opened in 1992 to commemorate the Holocaust "challenge visitors' perceptions of democracy, morality, social justice and human rights".[54]

Buddhism

Although the first concrete example of Buddhist settlement in Australia was in 1848, there has been speculation from some anthropologists that there may have been contact hundreds of years earlier. Buddhists began arriving in Australia in numbers during the goldrush of the 1850s, with an influx of Chinese miners. However, the population remained low until the 1960s. Buddhism is now one of the fastest-growing religions in Australia. Immigration from Asia has contributed to this, but some people of Anglo-Celtic origin have also converted. The three main traditions of Buddhism - Theravada, East Asian and Tibetan) - are now represented in Australia.[2]

According to the Australian census in 2006, Buddhism is the largest non-Christian religion in Australia, with 418,000 adherents, or 2.1% of the total population. It was also the fastest growing religion in terms of percentage, having increased its number of adherents by 109.6% since 1996.

The Nan Tien Temple, or Southern Paradise Temple in Wollongong, NSW, began construction in the early 1990s adopting the Chinese palace building style and is today the largest Buddhist temple in the Southern Hemisphere[55]. The Temple follows the Ven. Master Hsing Yun of the Fo Guang Shan Buddhist order.

Sikhism

Sikhs have been in Australia since the 1830s, initially coming to work as labourers in the cane fields and as cameleers, known as Ghans. At the turn of the century a number of them were working as hawkers, opening up stores. After World War I, Sikhs in Australia were given rights far greater than other Asians and made use of them by emigrating to Australia and working as labourers. As the decades passed they formed a sizable community in Woolgoolga, where the first Gurdwara, named the First Sikh Temple, was built. Following the end of the White Australia Policy there has been a great increase in the number of Sikhs from a number of countries including India, Malaysia, Fiji and the United Kingdom. The 2006 Australian Census shows about 26,500 followers,[56] up from 17,000 in 2001 and 12,000 in 1996[57].

Bahá'í

The Bahá'í faith in Australia has a long history and a growing visible presence in the country since 1922. A Bahá'í House of Worship exists in Sydney, dedicated on 17 September 1961 and opened to the public after four years of construction. The 1996 Australian Census lists Bahá'í membership at just under 9 thousand Bahá'ís.[57] The 2001 the 2nd edition of A Practical Reference to Religious Diversity for Operational Police and Emergency Services added the Bahá'í faith in its coverage of religions in Australia and noted the community had grown to over 11 thousand.[57] The Association of Religion Data Archives (relying on World Christian Encyclopedia) estimated some 17,700 Bahá'ís in 2005.[58]

No religion

Australia is one of the least devout nations in the developed world, with religion not described as a central part in many people's lives.[59] This view is especially prominent among Australia's youth, who were ranked as the least religious worldwide in a 2008 survey conducted by The Christian Science Monitor.[60] As of 2006, there are 3,706,555 people in Australia with purely secular beliefs, categorised by ABS as "No Religion". This category includes just 4 named sub-categories, namely agnosticism, atheism, Humanism and rationalism. A 5th sub-category is "No Religion, nfd" (nfd=no further definition).

According to earlier Australian Bureau of Statistics data, in 2001 15.5% of the Australian population identified themselves as having "No Religion" in a census question. This was 1.5% lower than the 1996 result but increased to 18.7% in the census in 2006.[61]

A popular replacement for Atheist during the 2001 Australian Census was "Jedi" (see also Jedi census phenomenon).

Despite non-theistic secularists representing nearly 20% of the Australian population, the Australian Bureau of Statistics does not provide information in the annual "1301.0 - Year Book Australia" on religious affiliation [62] as to how many people fall into each sub-category. Data on religious affiliation is only collected by the ABS at the five yearly population census.

Atheist interests in Australia are represented nationally by the Atheist Foundation of Australia. Humanist interests in Australia are represented nationally by the Council of Australian Humanist Societies. Rationalist interests in Australia are represented nationally by the Rationalist Society of Australia.

Other

The 2006 census[56] shows 53 listed groups down to 5000 members (most of them Christian denominations, many of them national versions like Greek and Serbian Orthodox). Of the smaller religions Pagan shows 15 thousand, Bahá'í 12 thousand, Wiccan at 8 thousand, Humanism about 7 thousand. Between 1 and 5 thousand, other than small Christian denominations, there are the following religions - Taoist, Druse, Nature Religion, Satanism, Zoroastrian, Rationalism, Creativity, Theosophy, Jainism, Pantheism, and Neopaganism (Neodruidism, Asatru, Gaia). In general, non-Christian religions, as well as those subscribing to no religion, have been experiencing a rise in proportion to the overall population.[63] With fewer classifications, data from 1996 and 2001 shows Aboriginal Spirituality decreasing from 7 thousand to 5 thousand while Bahá'í grows from just under 9 thousand to over 11 thousand and the rest of the "Other" category growing from about 69,000 to about 92,000.[57]

See also

- List of the largest churches in Australia

- A Practical Reference to Religious Diversity for Operational Police and Emergency Services

References

Specific references:

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Gladigau, Kristen; Ben West (April 2007). "Religious affiliation and moral conservatism in Australia and South Australia" (Portable Document Format). Flinders Social Monitor (8). ISSN 1834-3783. http://smpf.flinders.edu.au/docs/No8%20Apr%2007.pdf. Retrieved 2009-10-18.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 2.5 2.6 http://www.dfat.gov.au/facts/religion.html

- ↑ Australian Christian Lobby, Voice for values 2003 - 2008, http://www.acl.org.au/national/browse.stw?article_id=15561

- ↑ "Cultural diversity". 1301.0 - Year Book Australia, 2008. Australian Bureau of Statistics. 2008-02-07. http://www.abs.gov.au/ausstats/[email protected]/7d12b0f6763c78caca257061001cc588/636F496B2B943F12CA2573D200109DA9?opendocument. Retrieved 2010-02-15.

- ↑ Eliade, M., Australian Religions: An Introduction, Oxford University Press, London, 1973 ISBN 080140729x, p. 1.

- ↑ Berndt, R. M., Australian Aboriginal Religion, E. J. Brill, Leiden, 1974 ISBN 9004038612, pp. 4-5

- ↑ Aboriginal painting "Coming of the Macassan traders"

- ↑ Article about Islam in Australia from Connecticut College

- ↑ A History of Islam in Australia from islamfortoday.com

- ↑ Saint Augustine, "De Civitate Dei", xvi, 9. Quoted from Catholic Encyclopedia: Antipodes.

- ↑ ABC Boyer Lectures, 2004. Lecture 1: Antipodes

- ↑ Catholic Encyclopedia: Antipodes. There is also an article on JSTOR: John Carey, "Ireland and the Antipodes: The Heterodoxy of Virgil of Salzburg". Speculum, Vol. 64, No. 1 (Jan., 1989), pp. 1-10

- ↑ Jonathan Edwards, Sermons and Discourses 1720-1723, ed. Wilson H. Kimnach, The Works of Jonathan Edwards, vol. 10 (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1992), p.279. Quoted from http://rspas.anu.edu.au/pah/TransTasman/papers/Piggin_Stuart.pdf

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 14.2 "Marrying Out — Part One: Not in Front of the Altar". Hindsight. ABC Radio National. 11 October 2009. http://www.abc.net.au/rn/hindsight/stories/2009/2675480.htm. Retrieved 2009-10-18.

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 http://adbonline.anu.edu.au/biogs/A020018b.htm

- ↑ http://www.abs.gov.au/AUSSTATS/[email protected]/Previousproducts/9FA90AEC587590EDCA2571B00014B9B3?opendocument

- ↑ http://adbonline.anu.edu.au/biogs/A020299b.htm

- ↑ http://primeministers.naa.gov.au/primeministers/scullin/fast-facts.aspx

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 http://adbonline.anu.edu.au/biogs/A090439b.htm

- ↑ http://www.hreoc.gov.au/human_rights/religion/index.html Article 18 Freedom of religion and belief

- ↑ Executive Summary: Isma - Listen

- ↑ NCLS releases latest estimates of church attendance, National Church Life Survey, Media release, 28 February 2004

- ↑ Australia in US Department of State International Religious Freedom Report 2003

- ↑ http://www.cultureandrecreation.gov.au/articles/christmas/

- ↑ http://www.smh.com.au/news/world-youth-day/150000-celebrate-at-nations-biggest-mass/2008/07/15/1215887621840.html?page=2

- ↑ http://exwwwsvh.stvincents.com.au/index.php?option=com_content&task=view&id=132&Itemid=160

- ↑ http://www.marymackillop.org.au/marys-story/beginnings.cfm?loadref=2

- ↑ http://adbonline.anu.edu.au/biogs/A120339b.htm?hilite=david%3Bunaipon

- ↑ 29.0 29.1 http://adbonline.anu.edu.au/biogs/A100391b.htm

- ↑ http://adbonline.anu.edu.au/biogs/A080554b.htm?hilite=john%3Bflynn

- ↑ http://www.curriculum.edu.au/cce/nicholls,9156.html

- ↑ http://www.catholicaustralia.com.au/page.php?pg=austchurch-history

- ↑ http://www.ncca.org.au/about/story

- ↑ 20680-Religious Affiliation by Age - Time Series Statistics (1996, 2001, 2006 Census Years) - Australia from censusdata.abs.gov.au

- ↑ Morissey et al. (1993, 2001), Living Religion, Pearson Education Australia Pty Ltd, (Malaysia).

- ↑ Hussein Abdulwahid Ameen, 'Muslims in Our Near North', http://www.islamfortoday.com/australia03.htm#nearnorth, (viewed) 7 May 2008

- ↑ http://recollections.nma.gov.au/issues/vol_2_no2/notes_and_comments/australias_muslim_cameleer_heritage/

- ↑ http://www.multiculturalaustralia.edu.au/history/timeline/period/From-Assimilation-to-Multiculturalism

- ↑ http://www.refugeecouncil.org.au/arp/overview.html

- ↑ Muslim Australians

- ↑ http://www.timesonline.co.uk/tol/news/world/article7027240.ece

- ↑ Muslim leader blames women for sex attacks

- ↑ 43.0 43.1 http://www.theage.com.au/news/national/new-mufti-a-gentle-soul/2007/06/11/1181414178471.html?s_cid=rss_age

- ↑ http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/asia-pacific/8155240.stm

- ↑ Govt considers Muslim advisory body

- ↑ Muslim leaders back advisory body plan

- ↑ Whites fleeing racially mixed schools in Australia: report

- ↑ http://www.immi.gov.au/living-in-australia/a-diverse-australia/mcrg_report.pdf

- ↑ http://www.aph.gov.au/library/INTGUIDE/sp/muslim_australians.htm

- ↑ http://www.dfat.gov.au/geo/indonesia/indonesia_brief.html

- ↑ http://www.gallipolimosque.org.au/mosque_history.aspx?iPageID=5

- ↑ http://www.jewishcare.com.au/MintDigital.NET/JewishCare.aspx?xmlNode=1

- ↑ http://adbonline.anu.edu.au/biogs/A100533b.htm?hilite=john%3Bmonash

- ↑ http://www.sydneyjewishmuseum.com.au/About-Us/Overview/default.aspx

- ↑ http://www.nantien.org.au/en/about/history.asp

- ↑ 56.0 56.1 Census Table 2006 - 20680-Religious Affiliation (full classification list) by Sex - Australia

- ↑ 57.0 57.1 57.2 57.3 A Practical Reference to Religious Diversity for Operational Police and Emergency Services "2nd" edition

- ↑ "Most Baha'i Nations (2005)". QuickLists > Compare Nations > Religions >. The Association of Religion Data Archives. 2005. http://www.thearda.com/QuickLists/QuickList_40c.asp. Retrieved 2009-07-04.

- ↑ God's OK, it's just the religion bit we don't like Sydney Morning Herald

- ↑ Lampman, Jane. "Global survey: youths see spiritual dimension to life", The Christian Science Monitor, 2008. Retrieved on November 8, 2008.

- ↑ "Census figures show more Australians have no religion", Mark Schliebs, News.com.au, 26 July 2007.

- ↑ 1301.0 - Year Book Australia, 2006

- ↑ Census shows non-Christian religions continue to grow at a faster rate - Media Fact Sheet, June 27, 2007

General references:

- Terence Lovat, New Studies in Religion. Social Science Press pg 148 (2002)

- Berndt, R. M., Australian Aboriginal Religion, E. J. Brill, Leiden, 1974 ISBN 90-04-03861-2

- Eliade, M., Australian Religions: An Introduction, Oxford University Press, London, 1973 ISBN 0-8014-0729-X

- Australian Standard Classification of Religious Groups (ASCRG), 1266.0, 1996

- 1996 Census Dictionary - Religion category

- 2001 Census Dictionary - Religion category

- Year Book Australia, 2006. Religious Affiliation section

External links

- National Church Life Survey

- Australia in USA Department of State International Religious Freedom Report

- Australians Turning to Islam

|

|||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||